The Innocent Eye

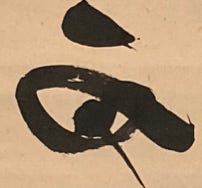

I was unfurling old Japanese scrolls obtained from an antique dealer who, having no market for old calligraphy, dumped them in a big box and gave them to me. Every scroll spoke with a different voice. Straightforward “clerical script,” wispy “running script,” strong and sure Zen blotches from a priestly hand. Many proclaimed militaristic virtues from the 1930s. Loyalty! Filial piety! Endurance! Banzai!

I struggled to read the twisting, curving lines. With me was Marcia Donahue, an artist friend who could not read characters at all. Yet she felt the energy of the brush strokes. Like seeing poodles in clouds, she imagined shapes and forms coalescing among the lines. I was fascinated. It was almost impossible for me to let go of my left-brain compulsion to understand the meaning of the characters and just focus on the shapes. So I asked her to draw what she imagined, with her innocent eye.

Eventually, with a bit of practice, I thought I might rediscover my innocent eye as well. Playful additions to old calligraphy on fusty scrolls rejuvenate them. Even a banal sentiment like “peace and harmony” (something an imperialist might have written), can change into a pair of butterflies, or dragons, or phoenixes.

I used to disdain people who felt entitled to analyze Chinese characters as if they were Rorschach ink blots, even though they couldn’t read them. Roland Barthes did so when he opined about Japanese culture, despite the fact that he could neither speak nor read the language. In effect, he made Japan a reflection of himself. To me this was sacrilege. I felt that brushed calligraphy (sho) is words, not pictures, and needs to be understood as such. This entails not merely knowing the printed form of a character, but the myriad ways it can be transformed in different calligraphic styles, from arcane “seal script” to wildly cursive “grass script.”

This is an ongoing study for me. I slowly attempt to decipher these old scrolls with help from scholarly friends. It seems strange, but once you learn what the character is, suddenly your eye sees that snarl of worms unmistakably as that character. The gibberish of a tangled line of ink now speaks its message clearly. I find this process of recognition hugely satisfying.

Yet there is no denying that the purely surface pattern of the brushstrokes, the only thing an innocent eye can relate to, has interest and beauty on its own. Post-WWII avant-garde Japanese artists sought to emphasize this in abstract calligraphic works where the powerful visual impact of the brushwork was in fact the point.

I think of hanging scrolls featuring sho as multilayered objects, each with its own social, artistic, literary, and philosophical elements. Anyone hanging a scroll in the tokonoma alcove in their home was making a statement about themselves—their beliefs, values, education, and taste.

This is why I love to study and read old cast-off scrolls. They are true voices from Japan’s past. I am now discovering that it is possible to play with them imaginatively too—adding yet another layer to these written voices.

In this project, The Innocent Eye, I have “mounted” the revamped scrolls virtually.

Liza Dalby

Berkeley, California